We have a large and widening divide between U.S. economic data and the rest of the world, and to spice things up we have no experience with a situation like this — “we” being the Fed, other central banks, all governments, and certainly analysts.

We have a large and widening divide between U.S. economic data and the rest of the world, and to spice things up we have no experience with a situation like this — “we” being the Fed, other central banks, all governments, and certainly analysts.

Experienced or not, markets are moving, and recent trading is at odds with most of the expectations of everyone on the list of players, above.

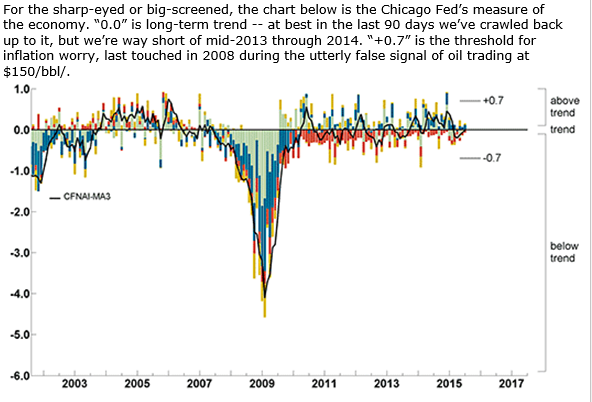

The U.S. is growing at a reasonable pace, but not accelerating; the rest of the world is slipping close to recession despite fantastic stimulus in Europe, Japan, and China.

The Fed and rates back in the ’90s

We do have experience with U.S. divergence from the rest, most recently 1997-1998, when the Fed was so concerned that it cut the cost of money, hoping the U.S. locomotive would pull the rest of the world. Those cuts came despite a roaring U.S. stock market and good GDP growth in place. Going farther back, the 1980s widespread defaults in Latin America exposed foolishness at U.S. banks which had to be papered over, but was never a serious economic threat here.

Even farther back, this cliché: “When the U.S. sneezes, the rest of the world catches cold.” But U.S. strength in the last century was so great that the rest of the world could catch pneumonia and we wouldn’t feel a thing.

That old world was convenient for our Fed. It had occasionally to manage the inevitable post-WW II decline in the dollar, but otherwise reacted only to domestic data.

Now? Holy smokes. The Fed’s normal duty is to lean against acceleration to intercept future inflation. The only aspect of the U.S. economy anywhere near capacity is the theoretical rate of unemployment — a tender spot for future inflation prospects, but inflation is not a problem anywhere on Earth.

Incipient deflation

Incipient deflation shouts from today’s markets. Gold is in free-fall, and so is the entire industrial metals complex, copper at 2009 levels (not a good year anywhere). Oil has broken $50 again going down. The currencies of commodity-producing “emerging nations” (an absurd misnomer for many — Brazil is as established an economy as any) are falling fast. In the last year the Aussie dollar has dropped from long-term near parity with the U.S. buck to $0.72 today.

It’s reasonable for the Fed to want to get above zero just as a preliminary move away from quantitative easing (QE). And it has a related agenda, to which Chair Yellen has repeatedly alluded: to raise rates slowly now, so not rapidly at some future moment.

There is no reason for a “rapid” rise

But there is no reason for a “rapid” rise, so what is she worried about? A crucial aspect of QE was the intentional boost of asset prices, directly stocks and bonds, and indirectly houses. Since we have never entered QE before, we hardly know how to leave it, and the Fed has reason to fear any sudden pulling of the rug from under assets. So begin ever-so-gently, and learn from the reaction to each step.

Two years ago Perfesser Bernanke triggered a rate spike and chaos just by saying the Fed would taper QE. We got over that, in part because the U.S. economy has underperformed every Fed forecast. Almost a year ago the Fed began its “liftoff” warnings. Even though our economy is still underperforming, the outside world took the warning seriously.

Currencies are the means of transmission. If we propose to raise our interest rates while others are cutting theirs, dollar up, others down.

Then this sequence. Japan has been a wreck for 25 years, but only in the last 18 months begun unimaginable QE devaluing the yen, which has forced all other Asian exporters into devaluing, or trouble, or both. Europe joined the QE party just six months ago, stimulus and devaluing, but hopelessly speared by the euro.

Now China. For reasons of pride it has refused to devalue the yuan, hurting its competitive position just as its credit-based stimulus clearly has run out the chain. Newest data extracted from earnings reports of U.S. exporters to China, and other independent sources suggest no growth there at all.

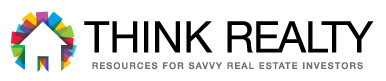

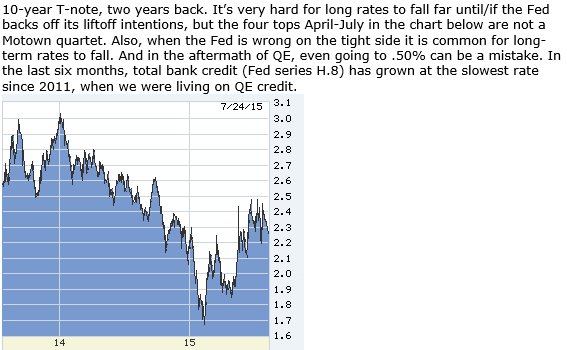

Dear Fed… you want to tighten into THAT? The bond market says “Uh-uh.” Here’s an irresponsible thought: the rate highs of 2015 may have passed.

——————————————–

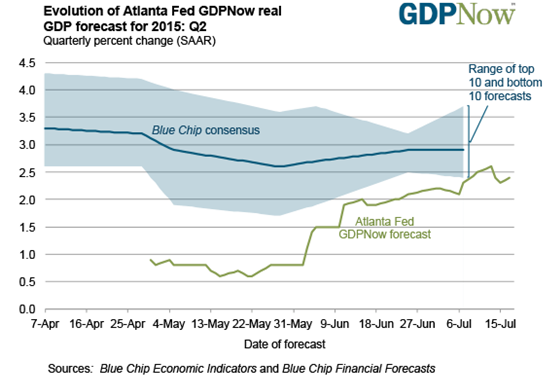

This Atlanta Fed engine, which updates continuously, has done well as a forecaster. We’re doing better than winter, but none of the rebound above 3% that the optimists were so sure of:

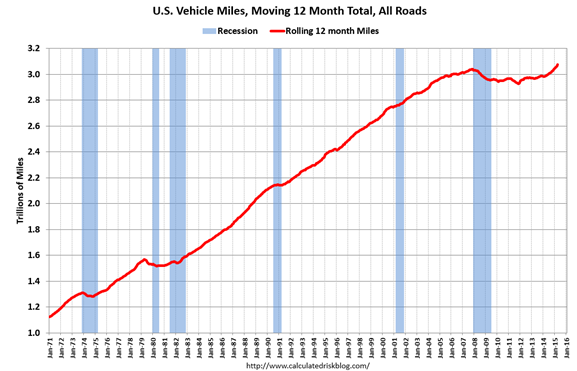

At last an uptick in vehicle miles driven. I assume more because of the drop in gas prices than great improvement in households. The chart goes back to 1971 (thank you, www.calculatedriskblog.com) — the spikes in gas prices in ’73 and ’79 were bigger than anything in the last decade (we stood in miles-long lines to buy gas), and the ’79-’82 recession was very bad, yet recovery quick. Different this time.

[hs_form id=”4″]

0 Comments