While Washington continues to address the crisis of people unable to pay rent, they have not addressed the issue of rental property owners who are unable to pay mortgages, which can create another “domino effect” of evictions and loss. The rental providers, therefore, suddenly find themselves thrown under the bus carrying the financial burden of this crisis: they are in effect subsidizing those who are not paying rent. Further, as a collective group, their burden lacks a representative voice in both federal and state governments.

Rethinking Community Development

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, we need to understand that the independent investor rental housing provider (with one, or even a handful of units, who provides necessary market-rent units to low-income communities) is in the midst of this pandemic wave, too. All involved have concerns of staying afloat. The notion of Community Development must begin to address needs of the rental industry as a whole, understanding segmented market supply and demand dynamics. If the low-income renter is vulnerable and at risk of eviction, we must also address the vulnerability of the small-unit count low-cost housing provider (referred throughout as “Independent(s)”), the majority of whom have one to three rental units.

The impact on small business during this pandemic is making headlines — revered as the backbone of the economy — and rightfully so. Independent housing providers, the backbone of low-cost market-rate housing, are also Small Business. Yet, it has become fashionable for renter activists and the politicians they support to vilify and blame rental owners, who are Small Business owners, for our nation’s housing woes. Why the contradiction?

The notion of low-cost rental housing as a business model within private industry is regarded as being part of an “extractive market.” This fallacy is an echo-chamber of groupthink perpetuated by many academics and renter activists with political support who believe government-run programs are the answer. This is patently false. In April’s Realty Matters Column, I revealed indisputable evidence to the contrary — that government-run programs are largely cause for the worsening problem.

That unfortunate thinking crowds the space for innovation and pragmatic free-market solutions to supply the necessary demand for affordable housing (both rentals and retail) faster — and at lower net cost to the taxpayer — with improved Community Development programs. We have to think about both supply and demand.

“Economic instability among tenants leads to economic instability among landlords” according to a HUD Office of Policy Development and Research Report (Garboden, Rosen, Greif, DeLuca, Edin, 2018).

Rethinking Evictions

Will circumstances of the pandemic offer a new lens for renter activists to finally realize that regardless of externalities, unpaid rent places independent housing providers at risk too?

In the midst of all this pain, both renters and housing providers are experiencing the effects of this pandemic. Lost jobs, lower wages, and unpaid rent provide a highly visible and contrasting story to the age-old narrative “Landlords are evil and are the blame for evictions.” In contrast, eviction is not the “fault” of the housing provider; it is a consequence of unpaid rent.

The pandemic puts an entire industry in jeopardy because it disproportionately affects those who are most at risk: low-income renters and their low-cost market-rate housing providers. As a group, Independents provide the largest proportion of all rentals and the highest proportion of low-cost market-rate rentals. Nationally, post-pandemic unpaid rent monies disproportionately impact independent investor rental providers more than “large” institutional rental housing providers.

The Real Consequences of Unpaid Rent

Independent rental housing providers often cannot absorb multiple months of unpaid rents from normally thin margins. This group often lacks access to additional capital, making them particularly vulnerable. Those who have some savings will likely exhaust it all to pay their mortgages and utilize whatever means of credit they have to “subsidize” unpaid rent, hopeful that better days will come. Why? They are optimists, intent to keep a bad situation from turning worse and will often stop at nothing to protect their credit scores. As funds deplete, the cascade begins: deferred maintenance or under-maintained rentals and an inability to pay the mortgages, property taxes, and utilities. Backlogged courts are further burdened with unpaid rent defenses due to lack of maintenance. Risk of criminal charges, fines, or even jail time percolate in the minds of independent providers who are scrambling for funds to keep the utilities on, even though rent is unpaid, where state retaliatory laws exist. With eviction protections in place, the unprotected independent rental provider, who relies on maintaining good credit scores, will burn through personal savings to protect their score and to stay afloat.

Pandemic-Induced Eviction Risk Is Overstated while Rental Delinquency Is Understated

We normally picture large institutional housing providers when we think of rental housing. And it is not surprising given the representation by the National Apartment Association and the National Multi-housing Council in Washington. However, the majority low-cost rental housing is typically owned and managed by independent housing providers who do not have a representative body to speak collectively about how the pandemic has impacted them. There are scores of renter-advocate organizations focused on evictions, while low-cost rental housing providers remain underrepresented. This group is disproportionately affected by the pandemic, and both the renter and the housing provider are financially vulnerable.

The eviction risk tallies are not reliable data sets for predicting outcome; they are largely derived from monthly opinions taken from a poll, and the monthly tallies are not additive as many of those organizations suggest. The total rent delinquency for some housing providers, say six or maybe nine months, may not be recoverable, causing long-lasting industry consequences at a scale never before experienced — all induced by the pandemic.

Behind the Numbers

The NAA representation for the rental housing industry is critical and much appreciated. The independent housing providers benefit greatly from their hard work. As an NAA member of their local affiliate, the Maryland Multi-housing Association (MMHA), I inquired to learn what their members are reporting. In general, state and national delinquency levels typically average 5-10 percent; the pandemic rocketed that range to 10-20 percent.

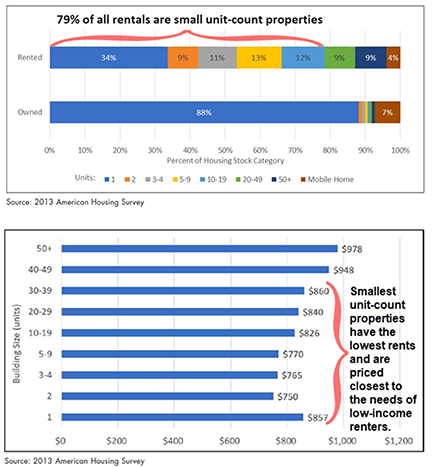

Class-C property delinquencies are greater, which is not surprising; however, the magnitude of the difference is telling. They are roughly twice as high again, or quadruple the normal average, and an increasing percentage of those renters now owe multiple months of rent. An apartment complex has the benefit of absorbing cash-flow reductions across multiple units that are still paying rent. The Independent provider of one or two units does not have that opportunity – and most of them are in the Class-B or Class-C property category. (See Graphics)

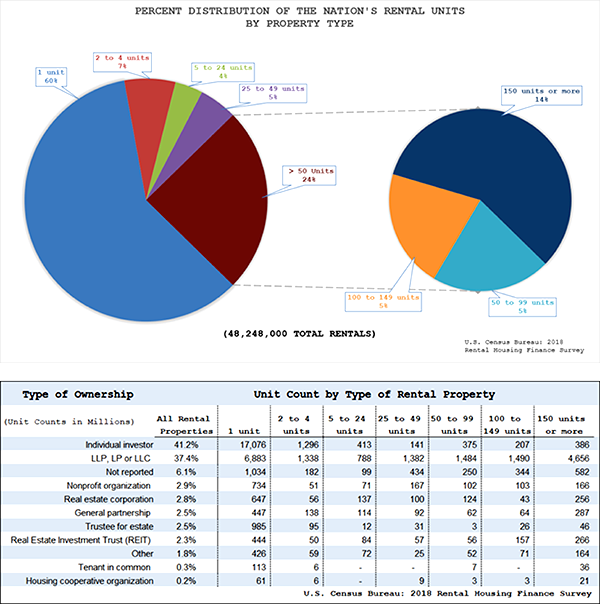

According to the newly released 2018 Rental Housing Finance Survey, 60 to 70 percent of available units, accounting for 29-34 million housing units on the market, are owned by independent investors; the majority own fewer than two units. Many place their ownership in an LLP, LP, LLC, or trust. (See Graphics)

This is significantly more than the conventional belief that half of all rental housing units are owned by small landlords. According to Pew Research, COVID-19 job and wage losses disproportionately affect those who rent low-cost market rate units, totaling half of lower-income Americans. These findings are consistent with the internal MMHA survey.

Adding It All Up

Bottom Line: It is a compound problem with depth beyond the obvious.

- Individual investors are the majority owners and operators of small unit-count properties.

- That category is the largest unit count of all rentals and household population.

- Those owners have limited funds and access to credit to cover missed rent payments.

- Those small-unit count rentals also contain the highest proportion of low-cost rental units.

- The renters of those very same low-cost units are vulnerable low-income households.

- They have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19 job or wage losses (half of all lower-income Americans).

- 75 percent of them do not have three months’ worth of emergency funds, and

- Surveys show that Class-C rental unit delinquency rate during the pandemic may be as high as quadruple the normal average.

The cascade continues with potential foreclosures and bankruptcies that remove availability of low-cost rental housing from what is already in undersupply, which further reduces available low-cost rentals that are normally in high demand which, in turn, may be a cause for increasing market rent prices at a time during high unemployment, etc.

Community Development Funding Is Needed to Shore up Instability

The pandemic changes the context through which to see the broken system and the pandemic demonstrates that an eviction may be neither party’s fault.

Unfortunately, the pandemic effect of sustained unpaid rent with increased delinquency for low-cost rentals may overstress the financial fragility in the system with potential cascading effects that permeate the industry, beginning with low-cost rentals. The pandemic effect may cause this precarious system to tip out of balance with unknown and unpredictable outcomes. With no aid relief package passed and in an election year, uncertainty lingers. The rental supply balance largely depends on independent investors to provide low-cost housing with small-unit count rentals – and we know now that they too are “vulnerable to the vicissitudes of the low-end rental market” as one HUD study phrased it. The system is frail, both parties are at risk and prefer no eviction.

Perhaps now, people will look through a new lens: evictions may not actually be the housing provider’s fault under most circumstances, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. As post-pandemic programs are assembled to heal and shore up hard-hit markets, it is time to reimagine “Community Development” as an innovation opportunity that collaborates with a collective community of independent housing providers to safeguard renters against funding the same flawed programs that have not met the demand. It will require courage to do something new, and embrace independent housing providers as well-regarded Small Business operators who graciously serve a critical need for tens of millions of low-income families: the backbone of humanity’s most essential need, housing.

Next month, a bold new plan and vision for the Rental Housing Industry will be revealed.

How are you managing during these challenging times?

Please complete our short survey. Let us know of any generosity or acts of kindness you have extended to your renter as they too are experiencing struggle during this COVID-19 pandemic.

Either scan the QR code, or navigate using the link below:

We need your good stories to counteract the predominant negative stories – and we will get your story out in a big way – stay tuned for next month!

For Column Notes, Resources and Language Translation for this Column, go to:

RealtyMatters.Online/Column/November-2020

0 Comments