Long-term rates have fallen back near the lows of the year, despite Wall Street salespeople trying to frighten investors about inflation and Fed tightening.

Long-term rates have fallen back near the lows of the year, despite Wall Street salespeople trying to frighten investors about inflation and Fed tightening.

That extraction of funding from crowds is indefensible, but our situation is confusing. Example: we would like to unseat Assad in Syria, and we wish bad things for the ISIS mob; this week Assad’s air force hit ISIS in Syria. Leaving this region to its own devices looks better all the time. Oil prices fell back to $105.

The top reason for the new drop in rates: the revision of 1st quarter GDP to a 2.9% contraction. The 1st quarter is ancient history, and optimists still blame winter weather, but a 2.9% dump is big. Throw out adjustments for inventories, trade, and ObamaCare spending, and the economy pooped along somewhere between 1% and zero.

The 2nd quarter has been widely expected to rebound at a 4% or 5% annual pace. It ends Monday, we’ll get the first estimates next month, and stripped of rebound oddities might — might — exceed 2%.

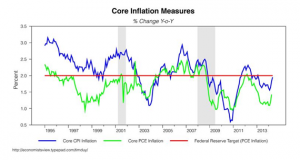

Inflation is key to the confusion

Personal income and spending in May were each supposed to rise .4%; income did, spending only .2%. That’s before inflation. After, by the Fed’s favorite “personal consumption expenditures,” spending fell .2% in April and .1% in May.

Yet financial media from here to Europe run on about central banks’ desire to raise the rate of inflation. Here in the U.S., Personal Consumption Expenditure inflation has crawled close to the target 2% (right now 1.8% year-over-year), but Fed Chair Janet Yellen is suspicious that the rise is just noise and we’re really closer to 1%.

Most people have figured out that inflation 1% or below forces some of us to repay debt in dollars worth more than the ones we borrowed — that’s what falling real income does to us. Not all of us, but at least half of us.

Most people have not figured out that rising inflation, even 3% or 4%, is not necessarily good news for the economy. Inflation is good if income rises with prices. Even better: incomes rising faster than prices. In a normal economy, expansions are driven by positive feedback, incomes pulling prices, the feedback so strong that it inevitably spirals out of control and the Fed must intervene by creating recessions.

But we are in a world jammed with excess labor and drowning in excess investment. Cheap labor substitutes for capital. This is not some proof of Marxism, although most on the left are trying; it is temporary, it’s end already in sight. China’s working-age pool began to shrink this decade, Japan’s and Europe’s last decade, and birth rates are falling below replacement everywhere except a few spots near the equator.

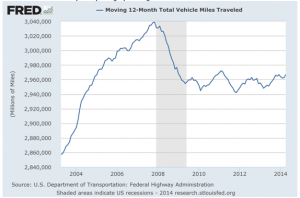

Higher prices with flat incomes are undermining, a contractionary force. Example: U.S. vehicle miles driven have never recovered from the spike to $3.50 gasoline.

Exception!! Houses. An amazing collection of financial people trying to analyze housing now assert that rising prices are a Bad Thing. Rose too fast last year, that’s why housing has slowed, they say.

This nonsense is perfect bull byproduct. In every U.S. expansion since WW II, rising prices of homes have been central to growth and runaway feedback. In recessions the cost of credit drops, stays low because it takes a long time for jobs to recover, deferring Fed intervention, and meanwhile affordability soars. Never higher than now. Only about 5% of the U.S. housing stock changes hands each year, and only the buyers must meet the test of affordability, but 100% of owners enjoy the wealth effect.

In this cycle housing purchasing power is limited for the two-thirds of our citizens crimped by flat incomes and rising consumer prices, working together to choke savings for a down payment, and further clamped for youth by student loans and too-tight mortgage credit. These are the reasons home price gains have flattened — April unchanged by Federal Housing Finance Agency measure — NOT because prices are too high or rising too fast.

Deficient income for too many of our people — that is the central issue. The Fed might nibble at some point, but will not bite until incomes enter that upward spiral.

———————————————–

10-year T-note, last 6 months. 2.50% pulls mortgages to 4.25%, even below. Click on charts to enlarge.

NOT going to sustain inflation until wages rise. Can’t.

Sounds crazy, but if inflation continues to rise, goes above Fed’s 2% target, it will tend to slow economy. That’s why the Fed is not on inflation-hair trigger.

For old folks, still determined to fight the last war…. Were the last 30 years the anomaly, or the 1973-79 run of oil from $3 to 412 and then to $33? (In real dollars, roughly $9 to $36, to $100.)

(Note: the next two charts have wildly different vertical scales, the first compact, the second exaggerated). From 2004 to 2005, retail gasoline rose from nearly 20 years at a buck-and-a-half to spikes at $3.00. The Great Recession held gas just under $3.00, still a huge increase, and not even fracking has knocked us under the $3.50 range.

Vehicle miles used to rise with, or faster than population. US population has risen 15 million since 2008. Vehicle miles are dead flat, showing on-going painful adjustment to doubled cost. Certainly still pulling spending from other sectors.

[hs_form id=”4″]

0 Comments